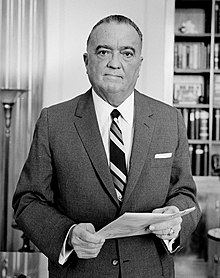

J. Edgar’s long reign taught us one fundamental thing. It is a bad idea having one person in charge of an investigating agency for 48 years. Some called him the closest thing to a dictator America has ever seen. We will never know the extent of his evil doings because his secretary. Helen Gandy, who had worked with him for 54 years, and close friend and daily companion of over 40 years, Clyde Tolson, took control of all his files and destroyed them.

J. Edgar’s long reign taught us one fundamental thing. It is a bad idea having one person in charge of an investigating agency for 48 years. Some called him the closest thing to a dictator America has ever seen. We will never know the extent of his evil doings because his secretary. Helen Gandy, who had worked with him for 54 years, and close friend and daily companion of over 40 years, Clyde Tolson, took control of all his files and destroyed them.

Once J. Edgar was no longer in power the FBI had to adjust to his absence. As expected, there were several pretenders to the throne among them Mark Felt, also known as Deep Throat. Seeing the FBI vulnerable some in Congress ginned up enough courage to investigate it. The result was the formation of the Church Committee. The FBI was so revered that the idea Congress was thinking of looking at its actions was called treasonous by some.

The Church Committee’s report told of years of abuses by the FBI. One thing that came from it was a recommendation limiting the term of the FBI director to 8 years. Legislation was enacted limiting it to 10 years. We did not want to see another J. Edgar even though it is uncertain his spirit has ever gone away.

The present FBI Director is Robert S. Mueller III. He was appointed on August 2, 2001. OOPS! Hold on! You just said the term limit was ten years. What’s Mueller still doing there?

It seems we have short memories in the US. Obama asked for him to be reappointed for two more years because of the ongoing threats to our country from terrorism. Since that threat will never go away, will that be the same fate of Mueller?

Some objected to extending Mueller. The ACLU reminded Congress why the limit was put in place in the first place Senator Charles Grassley said: “This is an extraordinary step that the Senate has taken. Thirty-five years ago Congress limited the FBI’s director’s term to one, 10-year appointment as an important safeguard against improper political influence and abuses of the past.” It was so extraordinary he nevertheless voted for the extension as did 99 other Senators. The House passed the bill on a voice vote. The limitation was easily tossed out the window.

Under Mueller the FBI has engaged in a number of abuses as set out in the ACLU’s opposition. So one has to wonder, are we creating another J. Edgar? The reason J. Edgar kept getting reappointed was he had something on every one; no one dared take him on, not even Congress but least of all the president. Is it the same reason for Mueller?

We don’t know whether Mueller walked into Obama’s office and dropped a dossier on his desk and then suggested he’d like to stay in office. Mueller seems cut from a different cloth than J. Edgar. His background is more diverse. He’s in his late 60s so he’d be hard pressed to add another 36 years to his tenure. Mueller’s a Marine officer and a Vietnam a combat veteran with a bronze star. (That gives me some comfort because of my tendency to have a bias for Marines despite Lee Harvey Oswald.)

I have a couple of problems with Mueller’s extension. I don’t believe that he has changed the FBI’s culture. Much of the secrecy and disregard for the laws still seems to continue.

But the main reason is the Mueller precedent may be used for someone more Hoover-like. We will be heading down the same slippery slope again.

I will show later that it appears Congress lives in great fear of the FBI. Hoover lived in the time before internet and before the endless war on terror. The FBI has gathered unto itself vasts amount of more power since that time. For instance, a mere letter (euphemistically entitled National Security Letter) written by any agent without outside oversight allows an agent to view all our financial and personal records held by others without our knowledge.

During Hoover’s era the FBI had mail opening operations which the Church Committee noted violated both our First and Fourth Amendment rights. The committee went on to note that the FBI “acted to protect a country whose laws and traditions gave every indication that it was not to be “protected” in such a fashion.”

Times they are changing. We no longer have the constitutional protection of being secure in our papers. Our courts have acquiesced in the diminishing of our rights. That is why we need our national police, the FBI, to be not only seen to be, but actually to be, pure as Caesar’s wife.

From: Flynn Edward [mailto:[email protected]]

Sent: Sunday, April 29, 2012 10:30 PM

To: Flynn Ed

Subject: Vietnam

Below is a rare insight into a critical turning point for America: the briefing to Lyndon Johnson that sealed the fate of more than 55,000 lives of American soldiers and wasted the vast treasure of the USA. The story is short, compelling and unforgettable.

Lt. Gen. Charles Cooper, USMC (Ret.) is the author of “Cheers and Tears: A Marine’s Story of Combat in Peace and War” (2002), from which this article is excerpted. The article recently drew national attention after it was posted on MILINET.

“The President will see you at two o’clock.”

It was a beautiful fall day in November of 1965; early in the Vietnam War-too beautiful a day to be what many of us, anticipating it, had been calling “the day of reckoning.” We didn’t know how accurate that label would be.

The Pentagon is a busy place. Its workday starts early-especially if, as the expression goes, “there’s a war on.” By seven o’clock, the staff of Admiral David L. McDonald, the Navy’s senior admiral and Chief of Naval Operations, had started to work. Shortly after seven, Admiral McDonald arrived and began making final preparations for a meeting with President Lyndon Baines Johnson.

The Vietnam War was in its first year, and its uncertain direction troubled Admiral McDonald and the other service chiefs. They’d had a number of disagreements with Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara about strategy, and had finally requested a private meeting with the Commander in Chief-a perfectly legitimate procedure. Now, after many delays, the Joint Chiefs were finally to have that meeting. They hoped it would determine whether the US military would continue its seemingly directionless buildup to fight a protracted ground war, or take bold measures that would bring the war to an early and victorious end. The bold measures they would propose were to apply massive air power to the head of the enemy, Hanoi, and to close North Vietnam’s harbors by mining them.

The situation was not a simple one, and for several reasons. The most important reason was that North Vietnam’s neighbor to the north was communist China. Only 12 years had passed since the Korean War had ended in stalemate. The aggressors in that war had been the North Koreans. When the North Koreans’ defeat had appeared to be inevitable, communist China had sent hundreds of thousands of its Peoples’ Liberation Army “volunteers” to the rescue.

Now, in this new war, the North Vietnamese aggressor had the logistic support of the Soviet Union and, more to the point, of neighboring communist China. Although we had the air and naval forces with which to paralyze North Vietnam, we had to consider the possible reactions of the Chinese and the Russians.

Both China and the Soviet Union had pledged to support North Vietnam in the “war of national liberation” it was fighting to reunite the divided country, and both had the wherewithal to cause major problems. An important unknown was what the Russians would do if prevented from delivering goods to their communist protege in Hanoi. A more important question concerned communist China, next-door neighbor to North Vietnam. How would the Chinese react to a massive pummeling of their ally? More specifically, would they enter the war as they had done in North Korea? Or would they let the Vietnamese, for centuries a traditional enemy, fend for themselves? The service chiefs had considered these and similar questions, and had also asked the Central Intelligence Agency for answers and estimates.

The CIA was of little help, though it produced reams of text, executive summaries of the texts, and briefs of the executive summaries-all top secret, all extremely sensitive, and all of little use. The principal conclusion was that it was impossible to predict with any accuracy what the Chinese or Russians might do.

Despite the lack of a clear-cut intelligence estimate, Admiral McDonald and the other Joint Chiefs did what they were paid to do and reached a conclusion. They decided unanimously that the risk of the Chinese or Soviets reacting to massive US measures taken in North Vietnam was acceptably low, but only if we acted without delay. Unfortunately, the Secretary of Defense and his coterie of civilian “whiz kids” did not agree with the Joint Chiefs, and McNamara and his people were the ones who were actually steering military strategy. In the view of the Joint Chiefs, the United States was piling on forces in Vietnam without understanding the consequences. In the view of McNamara and his civilian team, we were doing the right thing. This was the fundamental dispute that had caused the Chiefs to request the seldom-used private audience with the Commander in Chief in order to present their military recommendations directly to him. McNamara had finally granted their request.

The 1965 Joint Chiefs of Staff had ample combat experience. Each was serving in his third war. The Chairman was General Earle Wheeler, US Army, highly regarded by the other members.

General Harold Johnson was the Army Chief of Staff. A World War II prisoner of the Japanese, he was a soft-spoken, even-tempered, deeply religious man.

General John P. McConnell, Air Force Chief of Staff, was a native of Arkansas and a 1932 graduate of West Point.

The Commandant of the Marine Corps was General Wallace M. Greene, Jr., a slim, short, all-business Marine. General Greene was a Naval Academy graduate and a zealous protector of the Marine Corps concept of controlling its own air resources as part of an integrated air-ground team.

Last and by no means least was Admiral McDonald, a Georgia minister’s son, also a Naval Academy graduate, and a naval aviator. While Admiral McDonald was a most capable leader, he was also a reluctant warrior. He did not like what he saw emerging as a national commitment. He did not really want the US to get involved with land warfare, believing as he did that the Navy could apply sea power against North Vietnam very effectively by mining, blockading, and assisting in a bombing campaign, and in this way help to bring the war to a swift and satisfactory conclusion.

The Joint Chiefs intended that the prime topics of the meeting with the President would be naval matters-the mining and blockading of the port of Haiphong and naval support of a bombing campaign aimed at Hanoi. For that reason, the Navy was to furnish a briefing map, and that became my responsibility. We mounted a suitable map on a large piece of plywood, then coated it with clear acetate so that the chiefs could mark on it with grease pencils during the discussion. The whole thing weighed about 30 pounds.

The Military Office at the White House agreed to set up an easel in the Oval Office to hold the map. I would accompany Admiral McDonald to the White House with the map, put the map in place when the meeting started, then get out. There would be no strap-hangers at the military summit meeting with Lyndon Johnson.

The map and I joined Admiral McDonald in his staff car for the short drive to the White House, a drive that was memorable only because of the silence. My admiral was totally preoccupied.

The chiefs’ appointment with the President was for two o’clock, and Admiral McDonald and I arrived about 20 minutes early. The chiefs were ushered into a fairly large room across the hall from the Oval Office. I propped the map board on the arms of a fancy chair where all could view it, left two of the grease pencils in the tray attached to the bottom of the board, and stepped out into the corridor. One of the chiefs shut the door, and they conferred in private until someone on the White House staff interrupted them about fifteen minutes later. As they came out, I retrieved the map, and then joined them in the corridor outside the President’s office.

Precisely at two o’clock President Johnson emerged from the Oval Office and greeted the chiefs. He was all charm. He was also big: at three or more inches over six feet tall and something on the order of 250 pounds, he was bigger than any of the chiefs. He personally ushered them into his office, all the while delivering gracious and solicitous comments with a Texas accent far more pronounced than the one that came through when he spoke on television. Holding the map board as the chiefs entered, I peered between them, trying to find the easel. There was none. The President looked at me, grasped the situation at once, and invited me in, adding, “You can stand right over here.” I had become an easel-one with eyes and ears.

To the right of the door, not far inside the office, large windows framed evergreen bushes growing in a nearby garden. The President’s desk and several chairs were farther in, diagonally across the room from the windows. The President positioned me near the windows, then arranged the chiefs in a semicircle in front of the map and its human easel. He did not offer them seats: they stood, with those who were to speak-Wheeler, McDonald, and McConnell-standing nearest the President. Paradoxically, the two whose services were most affected by a continuation of the ground buildup in Vietnam-Generals Johnson and Greene-stood farthest from the President. President Johnson stood nearest the door, about five feet from the map.

In retrospect, the setup-the failure to have an easel in place, the positioning of the chiefs on the outer fringe of the office, the lack of seating-did not augur well. The chiefs had expected the meeting to be a short one, and it met that expectation. They also expected it to be of momentous import, and it met that expectation, too. Unfortunately, it also proved to be a meeting that was critical to the proper pursuit of what was to become the longest, most divisive, and least conclusive war in our nation’s history-a war that almost tore the nation apart.

As General Wheeler started talking, President Johnson peered at the map. In five minutes or so, the general summarized our entry into Vietnam, the current status of forces, and the purpose of the meeting. Then he thanked the President for having given his senior military advisers the opportunity to present their opinions and recommendations. Finally, he noted that although Secretary McNamara did not subscribe to their views, he did agree that a presidential-level decision was required. President Johnson, arms crossed, seemed to be listening carefully.

The essence of General Wheeler’s presentation was that we had come to an early moment of truth in our ever-increasing Vietnam involvement. We had to start using our principal strengths-air and naval power-to punish the North Vietnamese, or we would risk becoming involved in another protracted Asian ground war with no prospects of a satisfactory solution. Speaking for the chiefs, General Wheeler offered a bold course of action that would avoid protracted land warfare. He proposed that we isolate the major port of Haiphong through naval mining, blockade the rest of the North Vietnamese coastline, and simultaneously start bombing Hanoi with B-52’s.

General Wheeler then asked Admiral McDonald to describe how the Navy and Air Force would combine forces to mine the waters off Haiphong and establish a naval blockade. When Admiral McDonald finished, General McConnell added that speed of execution would be essential, and that we would have to make the North Vietnamese believe that we would increase the level of punishment if they did not sue for peace.

Normally, time dims our memories-but it hasn’t dimmed this one. My memory of Lyndon Johnson on that day remains crystal clear. While General Wheeler, Admiral McDonald, and General McConnell spoke, he seemed to be listening closely, communicating only with an occasional nod. When General McConnell finished, General Wheeler asked the President if he had any questions. Johnson waited a moment or so, then turned to Generals Johnson and Greene, who had remained silent during the briefing, and asked, “Do you fully support these ideas?” He followed with the thought that it was they who were providing the ground troops, in effect acknowledging that the Army and the Marines were the services that had most to gain or lose as a result of this discussion. Both generals indicated their agreement with the proposal. Seemingly deep in thought, President Johnson turned his back on them for a minute or so, then suddenly discarding the calm, patient demeanor he had maintained throughout the meeting, whirled to face them and exploded.

I almost dropped the map. He screamed obscenities, he cursed them personally, he ridiculed them for coming to his office with their “military advice.” Noting that it was he who was carrying the weight of the free world on his shoulders, he called them filthy names-shitheads, dumb shits, pompous assholes-and used “the F-word” as an adjective more freely than a Marine in boot camp would use it. He then accused them of trying to pass the buck for World War III to him. It was unnerving, degrading.

After the tantrum, he resumed the calm, relaxed manner he had displayed earlier and again folded his arms. It was as though he had punished them, cowed them, and would now control them. Using soft-spoken profanities, he said something to the effect that they all knew now that he did not care about their military advice. After disparaging their abilities, he added that he did expect their help.

He suggested that each one of them change places with him and assume that five incompetents had just made these “military recommendations.” He told them that he was going to let them go through what he had to go through when idiots gave him stupid advice, adding that he had the whole damn world to worry about, and it was time to “see what kind of guts you have.” He paused, as if to let it sink in. The silence was like a palpable solid, the tension like that in a drumhead. After thirty or forty seconds of this, he turned to General Wheeler and demanded that Wheeler say what he would do if he were the President of the United States.

General Wheeler took a deep breath before answering. He was not an easy man to shake: his calm response set the tone for the others. He had known coming in, as had the others that Lyndon Johnson was an exceptionally strong personality and a venal and vindictive man as well. He had known that the stakes were high, and now realized that McNamara had prepared Johnson carefully for this meeting, which had been a charade.

Looking President Johnson squarely in the eye, General Wheeler told him that he understood the tremendous pressure and sense of responsibility Johnson felt. He added that probably no other President in history had had to make a decision of this importance, and further cushioned his remarks by saying that no matter how much about the presidency he did understand, there were many things about it that only one human being could ever understand. General Wheeler closed his remarks by saying something very close to this: “You, Mr. President, are that one human being. I cannot take your place, think your thoughts, know all you know, and tell you what I would do if I were you. I can’t do it, Mr. President. No man can honestly do it. Respectfully, sir, it is your decision and yours alone.”

Apparently unmoved, Johnson asked each of the other Chiefs the same question. One at a time, they supported General Wheeler and his rationale. By now, my arms felt as though they were about to break. The map seemed to weigh a ton, but the end appeared to be near. General Greene was the last to speak.

When General Greene finished, President Johnson, who was nothing if not a skilled actor, looked sad for a moment, then suddenly erupted again, yelling and cursing, again using language that even a Marine seldom hears. He told them he was disgusted with their naive approach, and that he was not going to let some military idiots talk him into World War III. He ended the conference by shouting “Get the hell out of my office!”

The Joint Chiefs of Staff had done their duty. They knew that the nation was making a strategic military error, and despite the rebuffs of their civilian masters in the Pentagon, they had insisted on presenting the problem as they saw it to the highest authority and recommending solutions. They had done so, and they had been rebuffed. That authority had not only rejected their solutions, but had also insulted and demeaned them. As Admiral McDonald and I drove back to the Pentagon, he turned to me and said that he had known tough days in his life, and sad ones as well, but “. . . this has got to have been the worst experience I could ever imagine.”

The US involvement in Vietnam lasted another ten years. The irony is that it began to end only when President Richard Nixon, after some backstage maneuvering on the international scene, did precisely what the Joint Chiefs of Staff had recommended to President Johnson in 1965. Why had Johnson not only dismissed their recommendations, but also ridiculed them? It must have been that Johnson had lacked something. Maybe it was foresight or boldness. Maybe it was the sophistication and understanding it took to deal with complex international issues. Or, since he was clearly a bully, maybe what he lacked was courage. We will never know. But had General Wheeler and the others received a fair hearing, and had their recommendations received serious study, the United States may well have saved the lives of most of its more than 55,000 sons who died in a war that its major architect, Robert Strange McNamara, now considers to have been a tragic mistake.

Jimmy: That’s about what I expected from LBJ. It didn’t surprise me. I’ve always had problems with him. You see, he always wore that Silver Star in his lapel on his suit jacket. Yes, LBJ was awarded the Silver Stat, the nation’s third highest combat ribbon during WWII. You cannot imagine the great feat of heroism he performed to attain it. I suggest you read: http://www.b-26mhs.org/archives/manuscripts/lbj_fake_silverstar.html

You’ll understand why I feel like I do about him.

He did do a good job. He had his conviction vacated, recovered his pension and yes received a Presidential Pardon. Unfortunately it cost him his career, temporarily his freedom and twenty years of his life for just doing his job, the right way. Meanwhile his persecutors got away scott free all to protect their corrupt deal with the devil. Thanks for your response and I look forward to reading more of your posts, very informative and your upcoming book.

Good luck.

Mueller was the AUSA in Boston who prosecuted Nazzaro in the 1980’s who was setup by the FBI to protect Bulger on the Callahan murder and now Mueller is head of the FBI ?

I knew Mueller was the AUSA in Boston at that time. Other AUSAs were Mark Wolf, the judge in the Salemme case, and Jerry O’Sullivan the head of the Strike Force who gave Whitey and Stevie a pass. Judge Stearns was also an AUSA in Boston but that was somewhat later. I know nothing about Nazzarro as I mentioned but I did see a Richard Nazzarro got a presidential pardon by Bill Clinton in 2001. I’m a little reluctant at this time to go beyond the Whitey Bulger matters and I don’t think at this time I’d be able to justice to Mr. Nazzarro by getting into his matter especially since he seems to have done a good job representing himself. I thank you for your interest.